2025-09-08

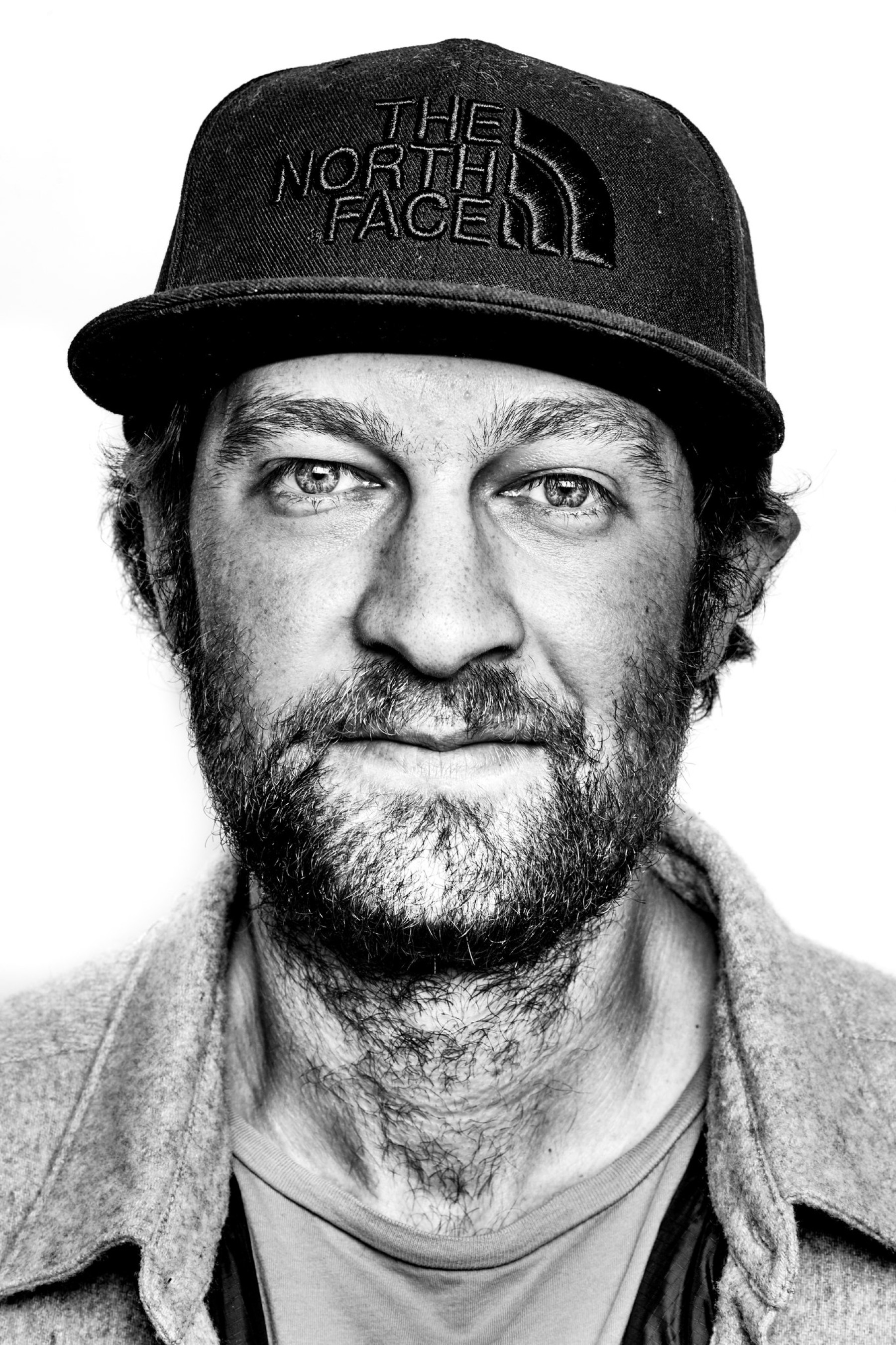

“I’m not looking for people to love Eloy de la Iglesia, but to understand him”

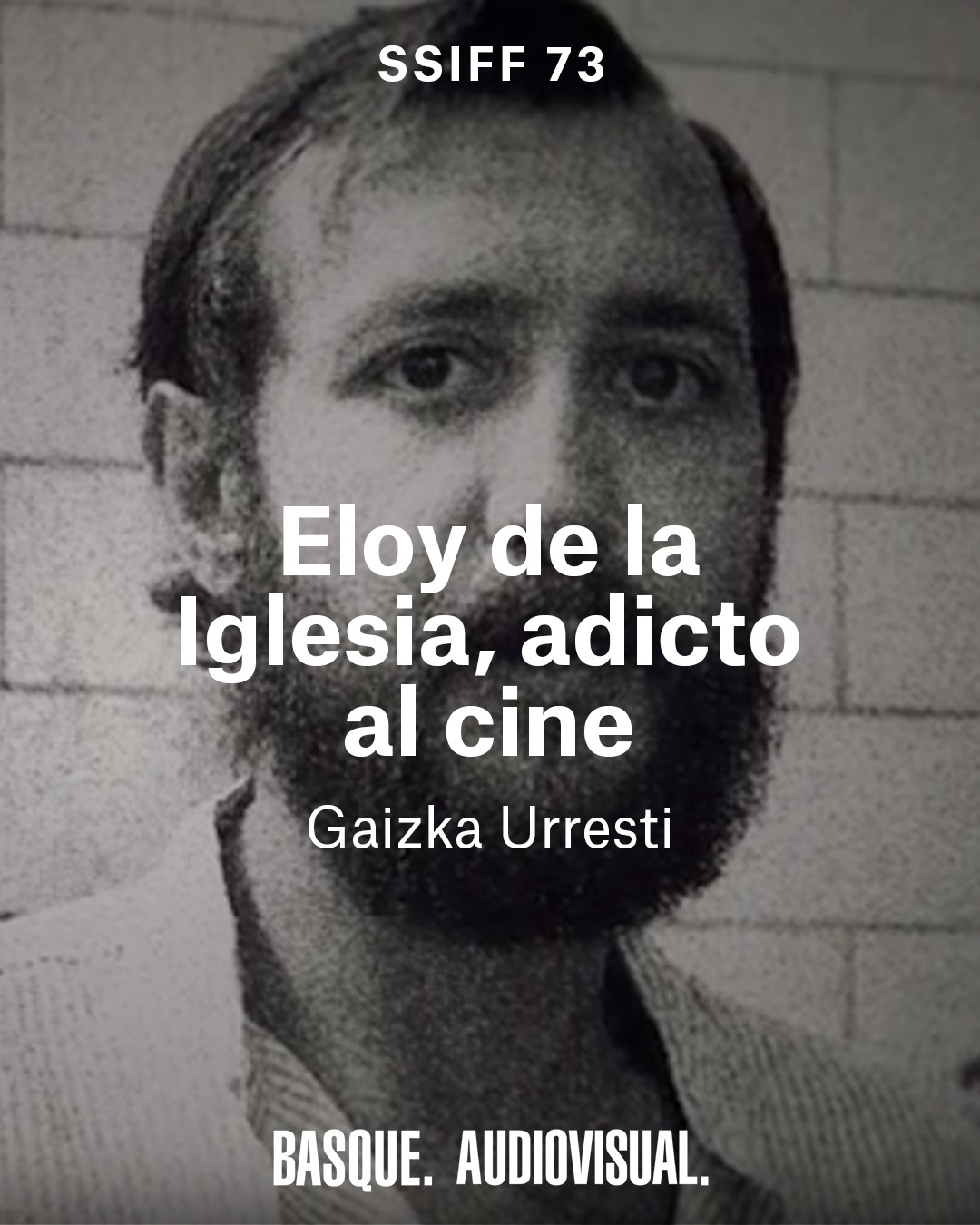

Filmmaker Gaizka Urresti is presenting ‘Eloy de la Iglesia, Film Addict’ at the San Sebastian Festival, a documentary that traces the lights and shadows of the Basque director. Urresti seeks to reclaim his legacy beyond prejudice, highlighting how his life and work reflect the tensions of late Francoism and Spain’s transition to democracy.

What was it that most attracted you to Eloy de la Iglesia, to the point of dedicating a documentary to him, and how did you decide to approach his figure?

This documentary has quite a long history. Oihana Olea, from Altube Films—niece of Pedro Olea, a friend of Eloy’s and producer of his last film—wanted to set it in motion after the director’s death. At first it was going to be directed by Diego Galán, a close friend of Eloy’s, but funding couldn’t be secured and, following his death, the project was left on hold.

Three years ago, TVE, the Basque Government and Madrid City Council joined the project, which allowed it to be revived. Oihana suggested it to me just after the Goya for ‘Labordeta’ in 2023, and I accepted, although financing it has been very difficult.

His biography, with its light and shade, seemed very appealing to me. From a dramatic point of view, it has a very powerful arc of transformation: his beginnings in cinema at a very young age, the clashes with censorship, success, his ties to the Communist Party, the experience of his homosexuality, his relationships with underage boys such as José Luis Manzano, his descent into the hell of heroin and his subsequent recovery. Moreover, his life and his films shed real light on the historical context of late Francoism and Spain’s transition to democracy.

My only previous connection with him was that my first film as producer and co-writer, ‘Chevrolet’, directed by Javier Maqua, was loosely inspired by his relationship with Manzano. Eloy didn’t like it because he said he had never lived on the streets, although his life and his cinema were intimately bound together.

I started from the prejudice of the ‘drug-addict director’ and from a body of work that had both shocked and unsettled me in my youth. Making this documentary placed me in an uncomfortable position, because until now I had always portrayed good people whom I admired. The question that stayed with me was: can you reclaim someone who is not ethically exemplary? In the end, I understood him, and I even grew to love him.

The documentary highlights the influence his work has had on both fellow creators and anonymous audiences. How is that legacy conveyed in the film?

I wouldn’t say legacy is the main focus, because the documentary is more about explaining his life through people who were very close to him, both personally and professionally. At first we considered including testimonies from contemporary filmmakers, but in the end we decided to concentrate on his own story.

That said, Gaspar Noé does appear. He never knew Eloy personally, but in 2023 he presented a full retrospective of his work at the Cinémathèque Française in Paris. There he admitted that he had discovered him thanks to the book published by the San Sebastián Festival in 1996, and he spoke passionately about his films.

What do you think new generations will discover in his films, and how relevant are his stories and characters today?

I have a revealing anecdote. During the editing process, I was working with three interns in their early twenties, and I showed them a rough cut. They were so surprised that they went online to check whether Eloy and his films were real.

I think young audiences will be struck by his transgression, the raw way he portrayed realities that were rarely represented. As Pepe Sacristán says in the documentary, I hope they don’t become too fascinated, because his life is not a model to follow. But it is crucial to understand the historical context: late Francoism, Franco’s death, the transition, the surge of freedoms, and also the rise of heroin and political and social violence. His films reflected all of that tension.

What were the main challenges you faced during the creation of the documentary, whether in terms of narrative, research, or production?

Narratively, we let Eloy speak for himself in interviews, although he tended to be elusive in personal matters. Many of the testimonies we collected were difficult to verify and sometimes offered conflicting versions of the same event, such as his relationship with Manzano. In those cases, I preferred to present contrasting perspectives so that the audience could draw their own conclusions. At times, I also chose to self-censor and leave out lurid details that added nothing.

Some of his collaborators declined to take part. Perhaps they didn’t want to revisit certain films, or their schedules made it difficult. In contrast, Pepe Sacristán once again demonstrated his generosity, finding time for everyone who reached out to him.

For the research, we relied on the few books published about him, especially ‘Conocer a Eloy’ and ‘Lejos de aquí’. In addition, we included their authors, Carlos Aguilar and Eduardo Fuembuena, as interviewees.

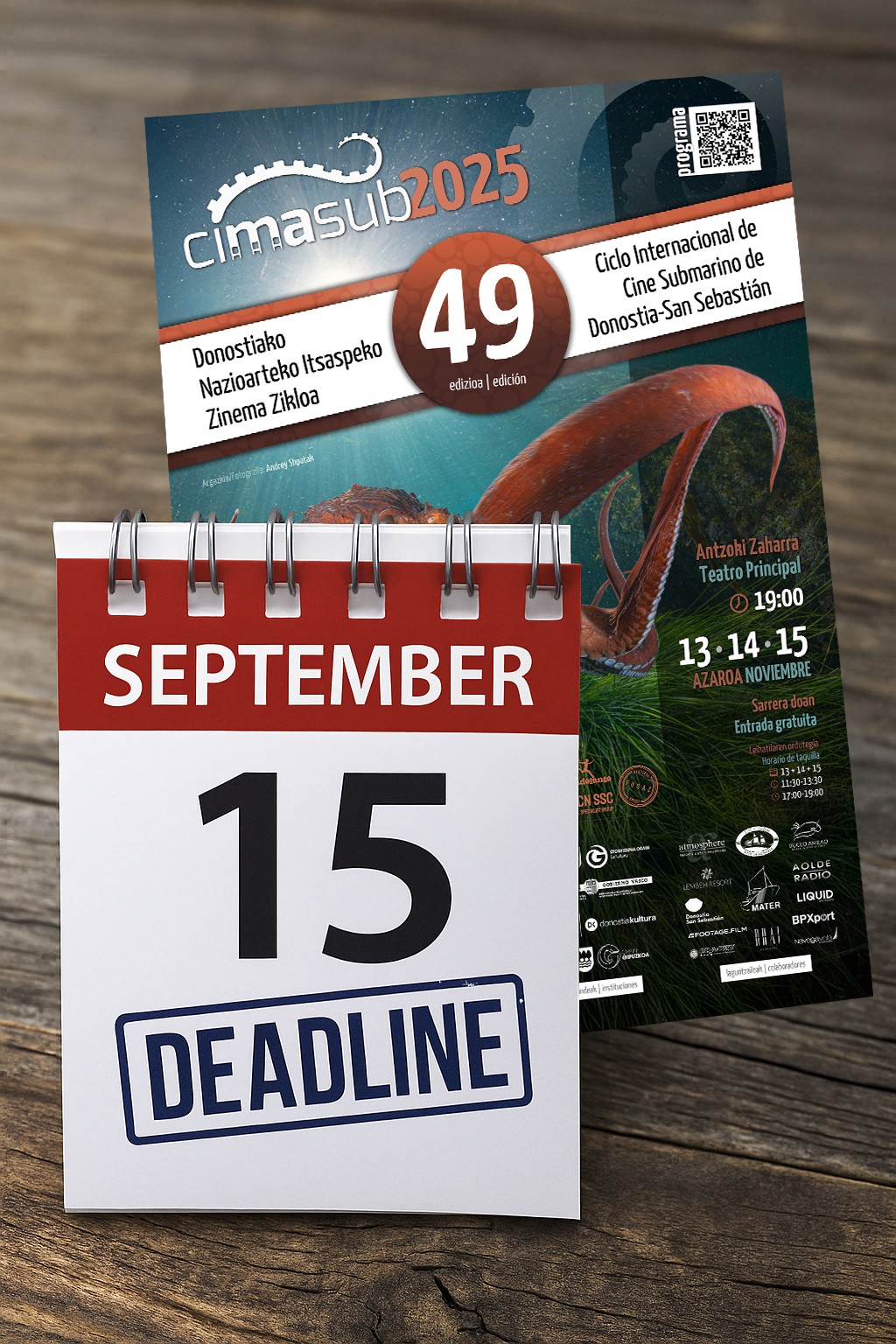

In terms of production, the lack of funding was a constant challenge: several national and regional institutions turned their backs on us. We also arrived at the San Sebastian Festival very close to the deadline: in May we had a first rough cut that didn’t convince us, and we rushed through May and June to finish it almost at the very last moment. Even in the summer we continued with final processes, because we were determined for the premiere to take place in Donosti.

Presenting this documentary at the San Sebastian Festival, so closely linked to auteur cinema and committed perspectives, what does it mean to you and what do you expect from the audience’s reaction?

We’re really thrilled to present it in San Sebastian, because as a teenager Eloy used to travel from Zarautz to attend the festival, and that’s where his love for cinema began. Later, he premiered key films here such as ‘El pico’ and ‘Otra vuelta de tuerca’. Most importantly, in 1996, the retrospective and the book published about him marked his personal and cinematic rediscovery. It’s the festival where Eloy would have loved his biography to premiere.

On a personal level, it’s also special because this is the first of my films as a director to compete in San Sebastián, alongside such talented filmmakers—many of them friends—like Alauda Ruiz de Azúa, Jose Mari Goenaga and Aitor Arregi, Alberto Rodríguez, Agustín Díaz Yanes, Asier Altuna, and others. It’s a real privilege.

From the audience, I hope they experience what I did: I’m not looking for them to love Eloy de la Iglesia, but to understand him. To see how he used cinema to rebel against oppression. More than rediscovering his work, I’m interested in reclaiming the person, with all his lights and shadows.

After its screening at the San Sebastian Festival, what will be the film’s journey?

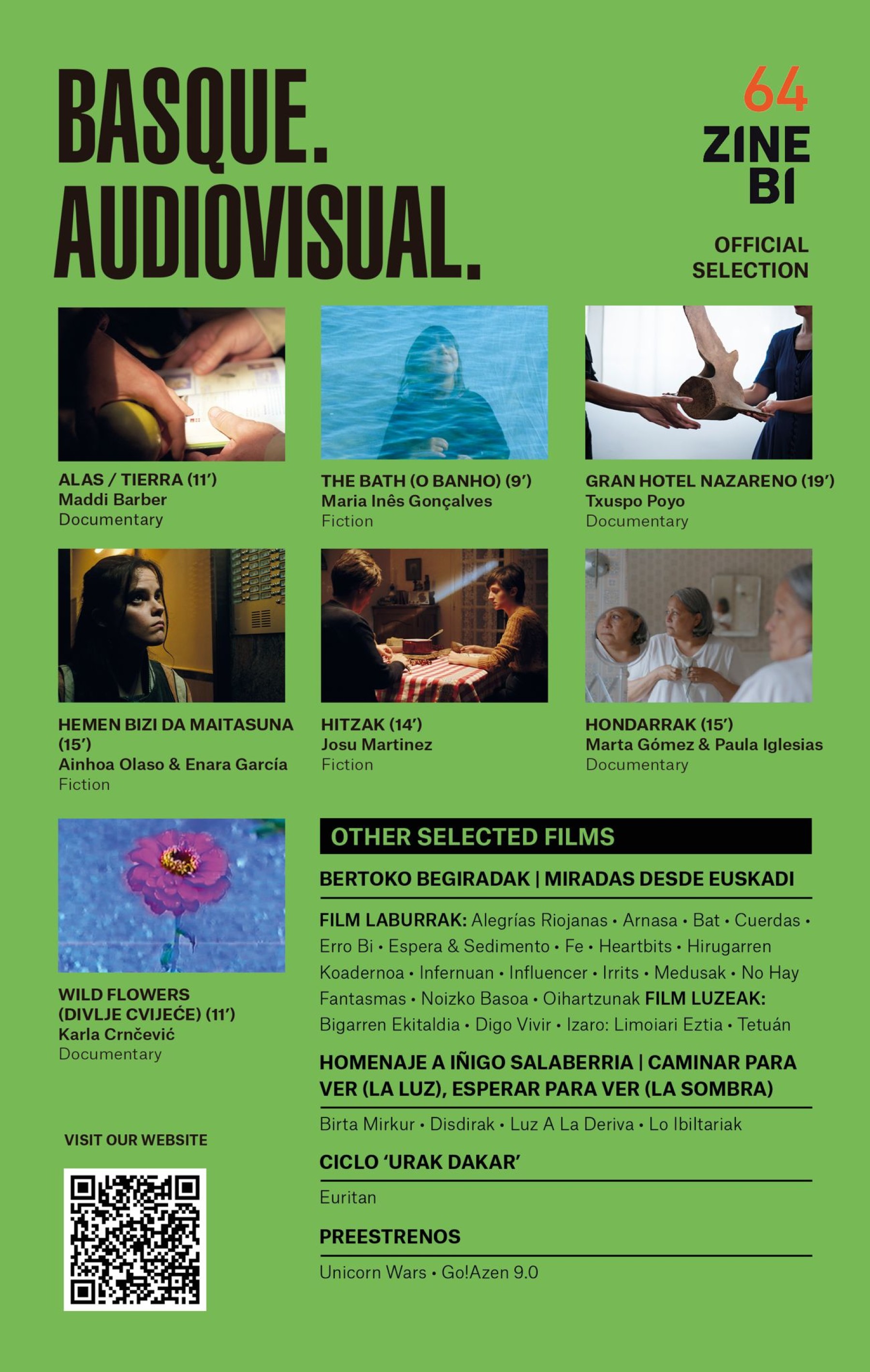

Its presence at the Sitges Festival, in the competing Documenta section, and at Zinebi in Bilbao, is already confirmed. We are awaiting confirmation from other national festivals before the commercial release at the end of November. Afterwards, we will begin its international circuit.

On television, it will be available on both Movistar and RTVE.