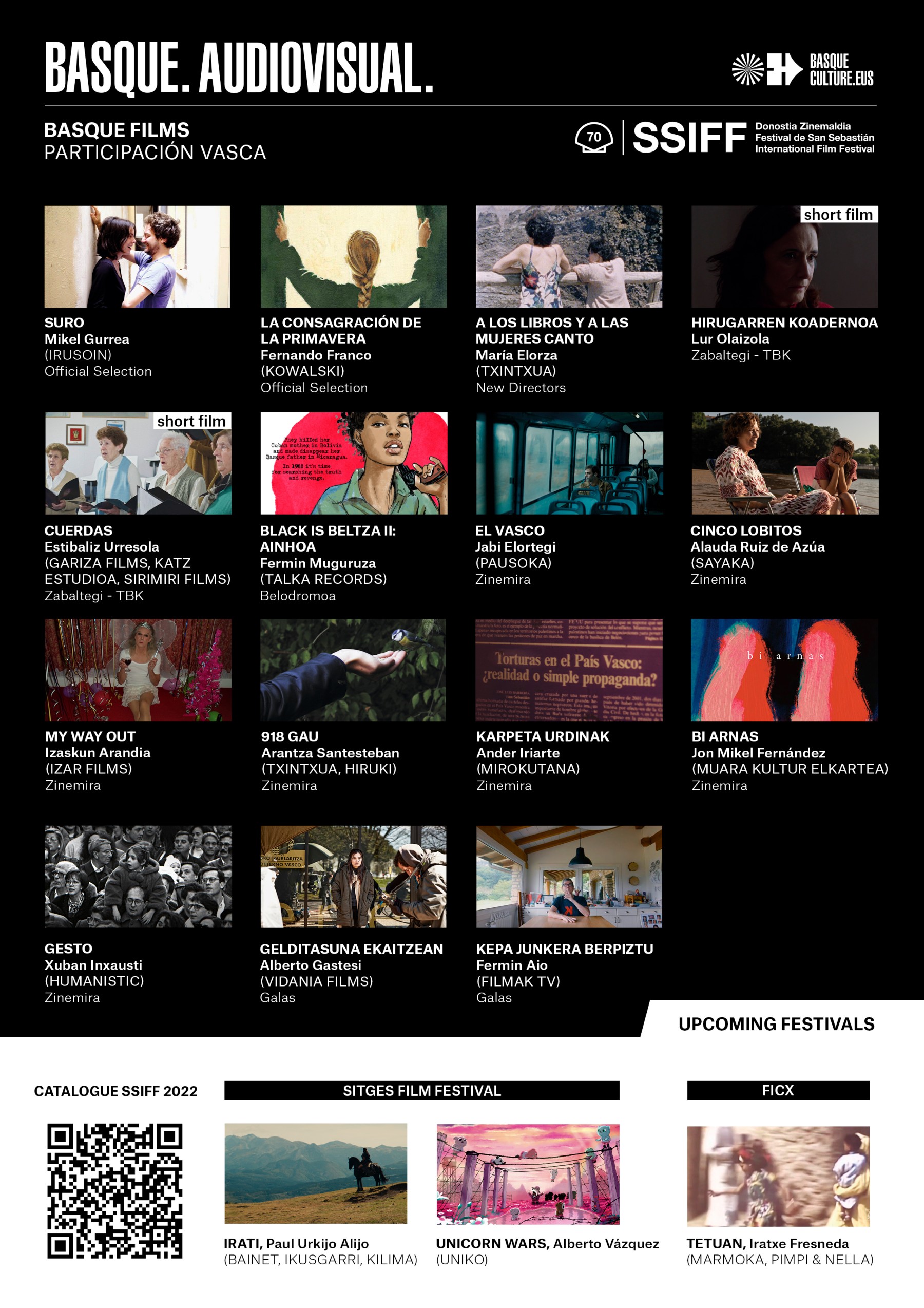

2025-11-21

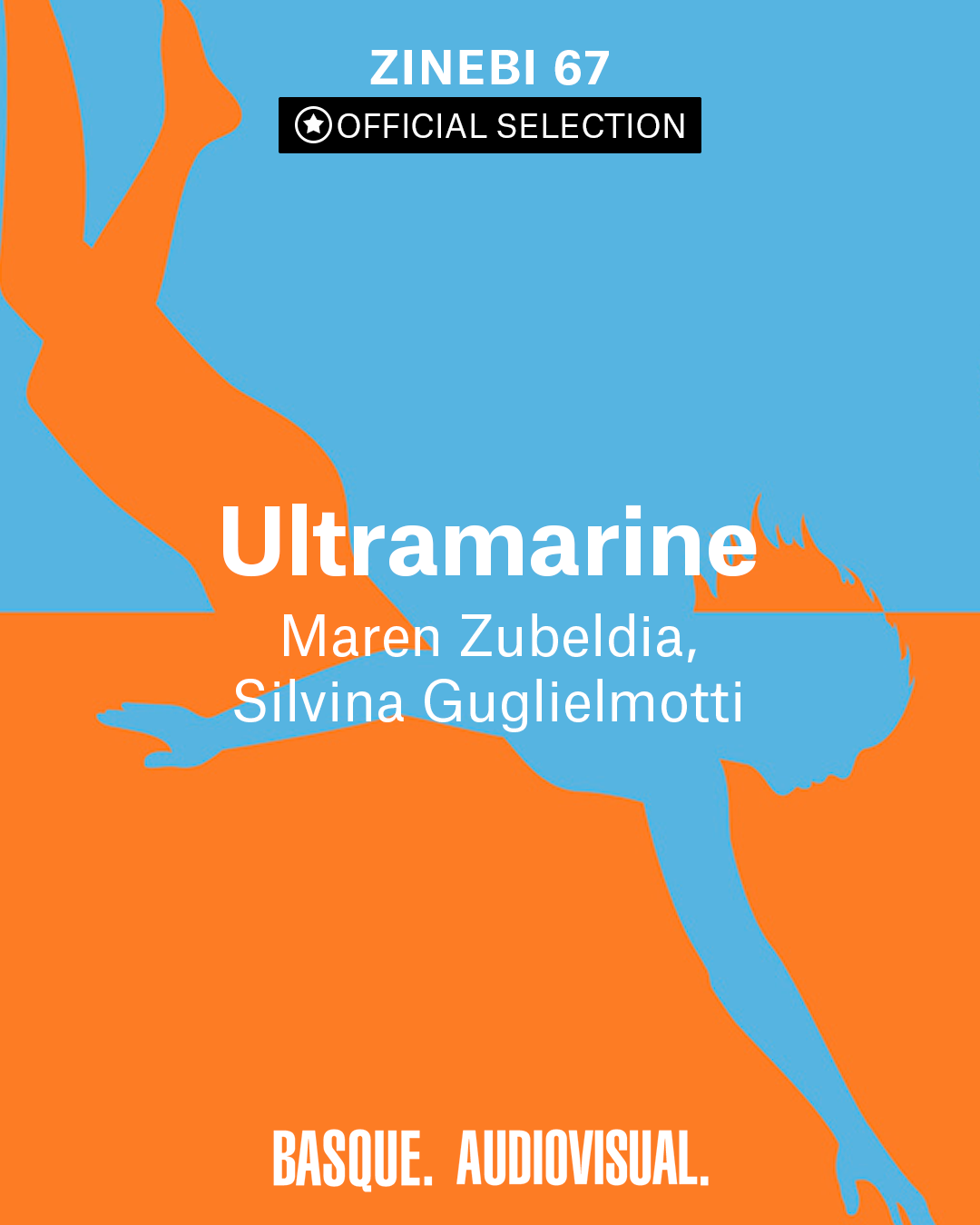

“I believe that the feeling the audience will have when they see ‘Ultramarine’ for the first time will be that of creating a new reference point”

‘Ultramarine’, the short film by Maren Zubeldia and Silvina Guglielmotti, arrives at Zinebi exploring non-binarity and questioning social traditions through the lens of a fishing village. In this interview, the directors discuss how the story came about, the challenges of filming —including high tides and flooded locations— and the excitement of premiering at home. They also explain the aim of their project: to create role models, spark debate, and provide a safe space for those who identify with the story.

How did the idea for ‘Ultramarine’ come about? What inspired you to tell this story?

Silvina: The idea for ‘Ultramarine’ came about because we had been working together in the audiovisual industry, in film. Maren, having participated in festivals like Zinegoak and being very involved in gender issues, told me that there was a great need to tell stories that allowed people to see themselves reflected in the experiences of others. From there, we started brainstorming ideas, and the question arose: what would it be like to live in a non-binary world? At first, we wanted to tell a story featuring an intersex character, but then we decided to focus on non-binarism because it seemed easier to develop within a short film. I’m very grateful to be working with Maren on this project for a generational reason: she’s much younger than me, and I come from a different generation, and that crossing of perspectives has enriched me immensely. I think it’s very interesting to be able to see both perspectives in the story.

Maren: Also, when we started the project, what connects Silvina and me in many ways is the sea. We both live on the coast. Silvina is from Buenos Aires but has been living in Ziburu for 20 years, and I’m from the San Sebastian dock, from a family of fishermen; I’m the fourth generation to be born or live in that house, and that has greatly influenced my upbringing and the way I see the world. When we began working on this non-binary character, we wanted to place them in a fishing village because it seemed like a setting closely tied to customs and tradition, and we thought it would be visually striking to situate our character in that context. That’s why it’s called ‘Ultramarino’: we started thinking of the corner shop (“ultramarinos”) as part of those traditions passed down from generation to generation, which we often think we are leaving behind. But then we realise that there are deeply ingrained traditions that can be very harmful for many people and bodies that don’t have space in a binary system.

Did you encounter any significant challenges or difficulties during filming?

Maren: Making films is very special for us because often you spend months or even years thinking about the project, how you’re going to shoot it, whether the weather will be favourable… and then you arrive on set and there might be a storm. We had spring tides, bad weather, wind… and many scenes were outdoors. We felt that frustration of: we’ve spent three years getting to shoot this project, and today of all days, the house floods.

Silvina: The day we were filming inside the house, it flooded due to an exceptionally high tide. The location was very special—a space suspended over the sea—which, for telling our story, became an absolute protagonist, almost like another member of the family. Suddenly, water started seeping up from the floor, and we were filming with that level of water, carrying the actors on our backs so they wouldn’t get wet, and lifting all the cables and equipment out of the way. Filming like that was quite dangerous, but we had to get the sequence done in the time we had. When we make films, the schedule is what it is and can’t be extended; that urgency of shooting then carries over into the story itself, and it shows. I think that being “invaded” by the sea also put the actors in a dramatic place that wouldn’t have existed without the high tide, and it worked in our favour to find something positive.

Another challenge was some tracking shots on a bicycle, which were very tricky; the bike carrying the camera got a puncture, and it was the shot introducing the character in our story. For us, cinema is also an art of renunciation, because you’re always thinking about how to get the project done in the time you have, giving up things you know would enhance it but simply can’t realise. It’s that mindset of saying, “let’s keep going, this is how the shoot is.” We always wish we had an extra day; in reality it’s two or three days, because there’s always something missing.

Being selected for a festival like Zinebi is a major achievement. What does it mean to you that ‘Ultramarine’ is part of this year’s edition?

Silvina: For us, being selected by Zinebi is a huge source of pride, particularly because of the sense of closeness and having attended as spectators ourselves, as people who go to and enjoy the festival. We feel local, and that’s always lovely—like premiering at home. It’s also a bit like the usual applause, whether from people who like you or don’t, but it feels like a community, and for me, that’s something worth highlighting.

Maren: For us, it’s very special that ‘Ultramarine’ can be seen for the first time at Zinebi, here in Euskal Herria, and with the local audience. I studied at the UPV in Leioa, and although I’m from San Sebastian and knew of the film festival there, when I arrived in Bilbao as a student, I learned that there was a very interesting short film and documentary festival. When you start studying film, you get closer to short films; it’s easier to think about making a short than a first feature. I have a strong connection with Zinebi, I know the team, and I’ve worked there on several editions, so having this premiere at home is very special.

We’ve also rounded out the experience because in 2022 we participated in the Aukera programme offered by HEMEN, won one of the awards, and received support from the Bilbao-based production company Doxa Producciones, with Zuri Goikoetxea and Ainhoa Andraka, who believed in our project. Gradually, we brought it to life, getting it off the ground, and our connection with Bilbao strengthened because the production company is from there. For us, it’s going to be very special, as many people—family and friends—participated in ‘Ultramarine’, getting involved and helping a lot, and we feel this is a way of celebrating that by premiering the film with all of them. This project is no longer just ours; it belongs to everyone, so we’re delighted to share it at Zinebi.

What reaction do you hope the audience will have when they watch the short film?

Maren: I think the feeling the audience will have when they see ‘Ultramarine’ for the first time will be that they are witnessing the creation of a new reference point. For example, if you know someone who is in this situation, or if you’ve heard of a person navigating non-binarity, this film exists precisely to make it clear to those around us that, very often, it’s not the bodies that are wrong. What’s wrong is the system, because the binary system doesn’t work. Every body is beautiful, valuable, lovely, and dear.

After Zinebi, what plans do you have for ‘Ultramarine’? What will its journey be?

Silvina: The journey of ‘Ultramarine’ has only just begun, and we’re confident it will be a long one and reach many people. From here, we’re heading to Gijón, then we’ll have its international premiere at Bogoshorts, and we’ve also been told it will be at Zinegoak. All of this is incredibly exciting for us.

Maren: Yes, it’s a programme within the Zinegoak festival, Bilbao’s LGTBI+ themed festival, and it’s aimed at secondary schools and colleges.

Silvina: We find it very interesting because it will spark debate, conversation, encounters, and disagreements, as it should. Above all, it will allow us to talk about the things that happen to us, that happen around us, or that exist without much visibility. As Maren said at one point, we have traditions so ingrained that we take them for granted without questioning them, and sometimes it’s necessary to reconsider them, to look at them from a certain distance and also from within, with perspective, to understand what what we’re telling really means in the moment we live in today.

Maren: And if, in those schools, there’s a student—if in those classrooms there’s someone who finds in our story a refuge or the feeling that they are not alone—that is precisely our intention.