2025-08-30

“I wouldn’t change a single frame"

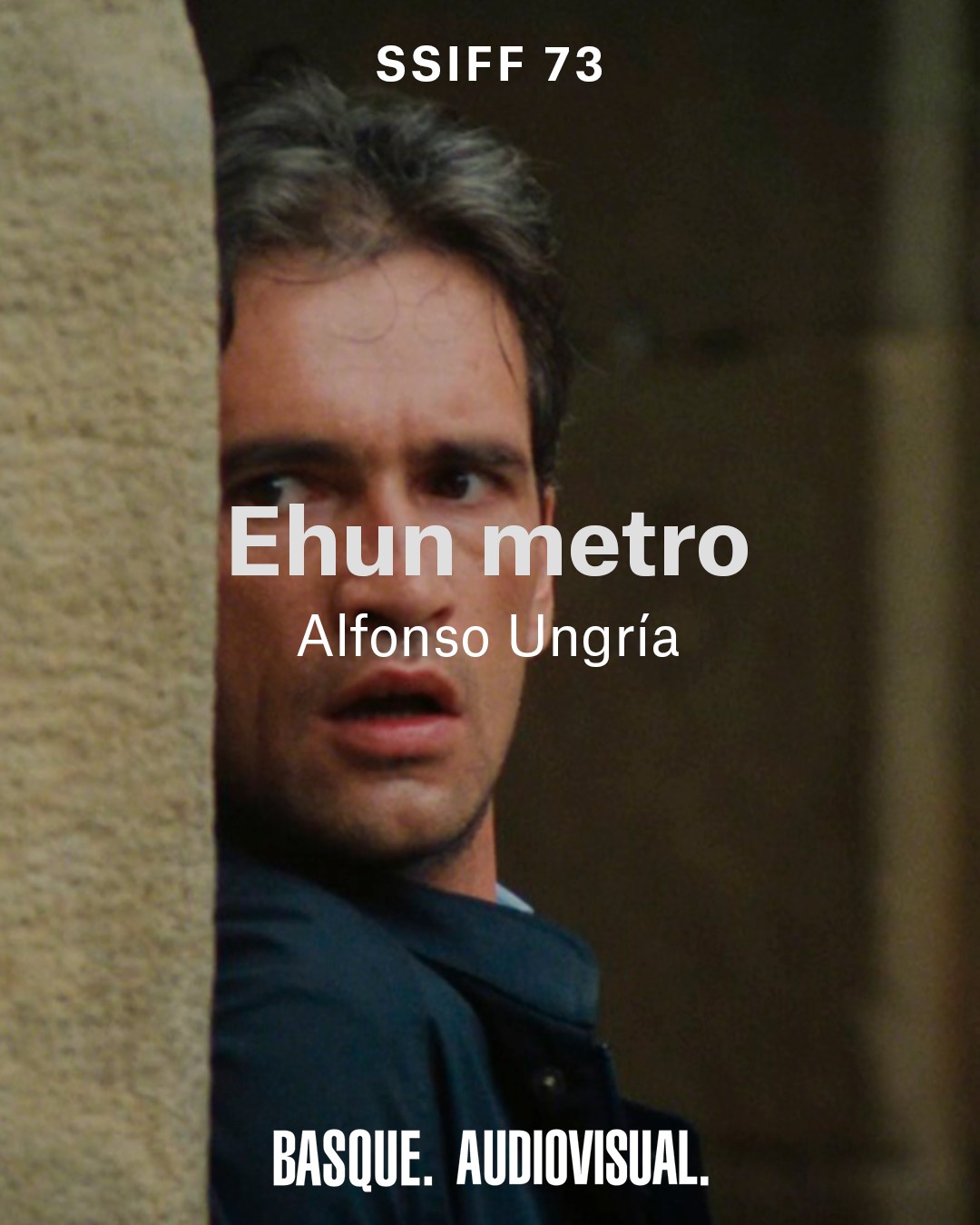

In 1985, Alfonso Ungría released ‘Ehun Metro’, an intense drama set in the turbulent Basque Country of the 1970s, during the Franco dictatorship. Filmed in Basque and based on a literary trilogy, the film tackled head-on issues such as political repression and torture, making it a unique work within Spanish cinema of the time. Almost four decades later, ‘Ehun Metro’ returns in a restored version to be screened in the Klasikoak section of the San Sebastian Film Festival. We spoke with Ungría about the origins of the project, its filming, the restoration of the film, and the emotional reunion with a city — Donostia — which, according to him, is the true protagonist of the story.

What inspired you to create Ehun Metro, and what made you want to tell its story?

Producers Ángel Amigo and Jesús Acín suggested I adapt that novel, a trilogy they wanted to film in Basque. I read it and was drawn to its dramatic conflict and the way it portrayed the society of San Sebastian. Having partly grown up in that city and with a lot of family there, it felt like a chance to reconnect with its experiences and characters. My only condition was that I would write the screenplay.

The film deals directly with torture and repression during the ‘Years of Lead’. Did you face any pressure or censorship during production or release?

The truth is, I didn’t face any pressure at all.

What challenges did you face in filming such a harrowing story that is still so recent?

I have always taken full responsibility for remaining absolutely faithful to the original work. As far as my own work is concerned, my sole aim is to create an artistic piece that is honest and imaginative. With that conviction, I hope the result will be a film of timeless value. Although I understand that, in every historical period, the reception, acceptance, and understanding of a work can vary depending on prevailing or accidental influences, fashions, and ideologies, such differences do not affect the work itself nor its creator; therefore, I do not take them into account.

As for the filming, I remember it as being perfect. Both the actors and the crew threw themselves into it with great enthusiasm.

There was only one major problem, which is now rather anecdotal: since the story takes place during the dictatorship, its main location, the Plaza de la Constitución (then Plaza de España), had to appear spotless—in the 1970 setting we were recreating—free of all the graffiti that covered its walls in 1985. We had to negotiate with all the Basque nationalist groups to ensure that, once cleaned, the walls wouldn’t be repainted during the shoot. Five minutes after wrapping, as we were striking the set, I saw a group of young people arriving, armed with cans of paint and brushes.

How did the idea to restore it come about?

From what I understand, the idea and its development have been carried out by the Basque Film Archive and EITB (the film’s owner). I hope that such an important initiative, aimed at preserving the cinematic heritage of our region, continues to be repeated. Once again, I want to express my gratitude, and to build on this positive momentum, I have already requested the restoration of La Conquista de Albania.

What was it like for you to reconnect with ‘Ehun Metro’ so many years later? Did you take part in the restoration process?

For its restoration in Bologna, I was invited by the aforementioned organisers to travel there to review and approve the resulting print. The whole process, for me, brought back the essential scents of San Sebastian. Because, after all—and beyond the dramatic journey of the main characters, which drives the film—the real protagonist is the city and its people. Its lights and shadows: its cinematic truth.

Do you think the restoration process allows certain films to be recovered and reinterpreted in a new social and political context?

If someone wants to ‘reinterpret’ an artistic work, that is their choice—equally free and personal. Cinema is about synthesis, about images. But some people, instead of engaging with images, focus on concepts. The work itself never changes its meaning, as that is intrinsic to its original and existential truth. As Hermann Hesse said, “In art, what matters is the timeless, not the fashionable.”

What would you say to young people watching ‘Ehun Metro’ for the first time today, who haven’t lived through that context?

The same as I would say to viewers of any age, gender, or background: watch it like any other film, without prejudice, and immerse yourself in the story and its images.

What does it mean to you that ‘Ehun Metro’ is being screened in the Klasikoak section of the San Sebastian Festival?

For me, it’s a source of pride and immense satisfaction whenever new audiences—and even more so when they are true film enthusiasts, like those attending the San Sebastian Festival—discover one of my films. A film like this was made with all the passion and effort I could pour into it, leaving nothing behind

Do you think today’s audiences will react differently to the story the film tells?

I have no idea.

You’ve worked in film, television, and documentaries. Where does ‘Ehun Metro’ fit within your career?

A very important one. On a personal level, it’s a flood of emotions, like any reunion with old loves: San Sebastian, my grandparents and my mother, my landscapes and my memories. Professionally, it’s one of my favourite films. During its production, I didn’t have to struggle against insensitive financiers or any censorship, as I was provided with sufficient resources and, most importantly, complete creative freedom.

If you could shoot it again today, would you change anything? Would you tell the story in the same way?

I wouldn’t change a single frame.