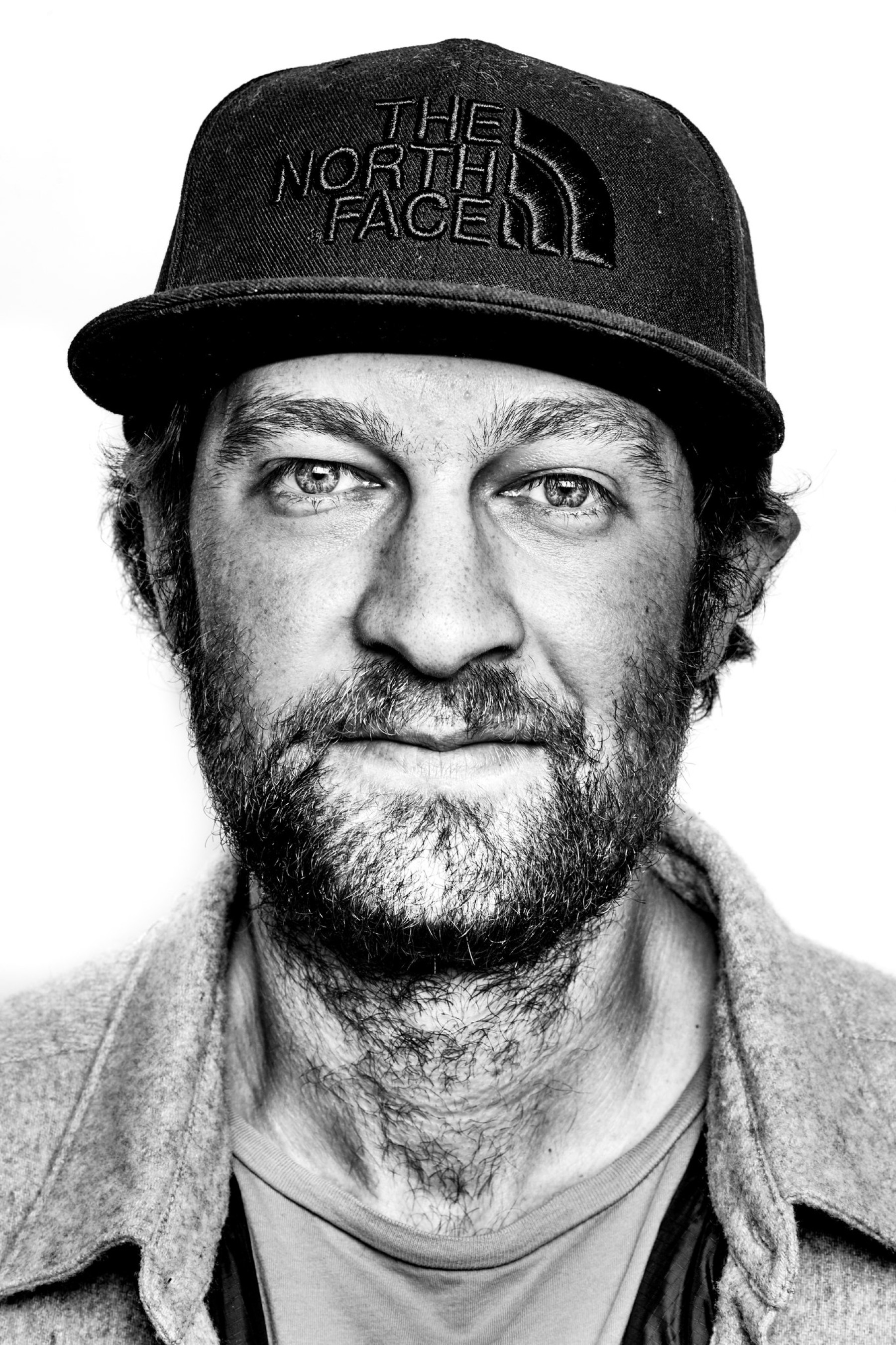

2025-09-02

“If ‘8’ is watched without thinking, only feeling, it ignites something deep within”

With a poetic and daring gaze, Julio Medem returns to the San Sebastian Festival to present 8 within the Made in Spain section. The film, which had already won over audiences in Malaga and garnered awards at international festivals, offers a journey spanning nearly a century through the lives of Octavio and Adela, two characters whose destinies intertwine as Spain passes through some of its most turbulent chapters. Eight sequence shots shape this intimate yet collective journey, in which Medem reflects on “the two Spains”, the weight of memory, and the utopian possibility of forgiveness as a way of laying to rest the ghosts of division. In this interview, the filmmaker speaks to us about the film’s singular language, its emotional and political charge, and the hope contained in its ending.

For those who haven’t seen it yet, what story does ‘8’ tell?

It tells the ninety years of life of Octavio and Adela, from their birth until they reach the age of ninety, in eight sequence shots — eight stretches in continuity and in the form of an “8” — while Spain unfolds behind them. Yet ‘8’, in its daring, risk-taking and free approach to language, is a tragic poem that begins and unfolds in verses of death, and ends with two verses of love.

What message did you want to convey to the audience with this film?

First, the most intimate: since the two protagonists are born almost at the same time and in two nearby places, it is suggested that their destinies, unbeknownst to them, will be connected and intertwined for life. Then comes the broader dimension — social, political: Octavio and Adela live for ninety years, and the eight chapters of the story take place at eight decisive moments in Spain’s history, between 1931 and 2021, yet always from the Spain each of them personally experiences. In this way, the intimate dramatic arc of each of their small lives is bound to the great dramatic arc of their country, Spain.

Through the relationship between Adela and Octavio, you speak of “the two Spains.” How would you define that representation through these characters?

The concept of “the two Spains” becomes evident from Chapter 2, in March 1939, at the end of the Spanish Civil War, when Octavio and Adela — eight-year-old children who do not yet know each other, and whose families belong to opposing sides — each lose their father at the hands of the other’s family. From this point onwards, ‘8’ can also be seen as an emotional reflection on Spain’s fratricidal tendencies.

The title is very symbolic: what does the 8 represent in the story you tell?

‘8’ is the silhouette that links the destinies of Adela and Octavio from birth, in the sense that it is two loops joined by a crossing point. In other words, each of the eight chapters — which may begin with Adela or with Octavio — keeps the two protagonists bound together by the outline of the 8, with a crossing shaped by chance, and yet separated, for they do not see each other and take a long time to become aware of the other’s existence.

The film presents the idea of a “ceremony of forgiveness.” How do you relate this ceremony to the historical division reflected in the protagonists?

The ceremony of forgiveness takes place at the end of Chapter 7, after a violent clash between Real Madrid and Barça supporters, with a fatal outcome for both sides. From this second climax of fratricide (the first being the Civil War), the story — if we consider Spain’s political reality — would seem destined to move towards a point of no return, to a new war. Yet ‘8’ proposes “the ceremony of forgiveness”: knowing how to ask forgiveness of the other, and the other knowing how to forgive. It is, of course, a utopia, with a clear political message — the courage to imagine reconciliation.

‘8’ spans almost a century of history. How do you think those ghosts of division have evolved in Spanish society?

During the transition to democracy, it seemed that the ghosts of confrontation — of that age-old war between Spanish brothers — were fading away, but in the 1990s they began to reawaken, until in the past decade they have threatened the worst once again. Hence in ‘8’ the utopia of forgiveness is proposed, leading into the late — yet deeply moving — love story between Adela and Octavio. The truest meaning and the finest ending for ‘8’.

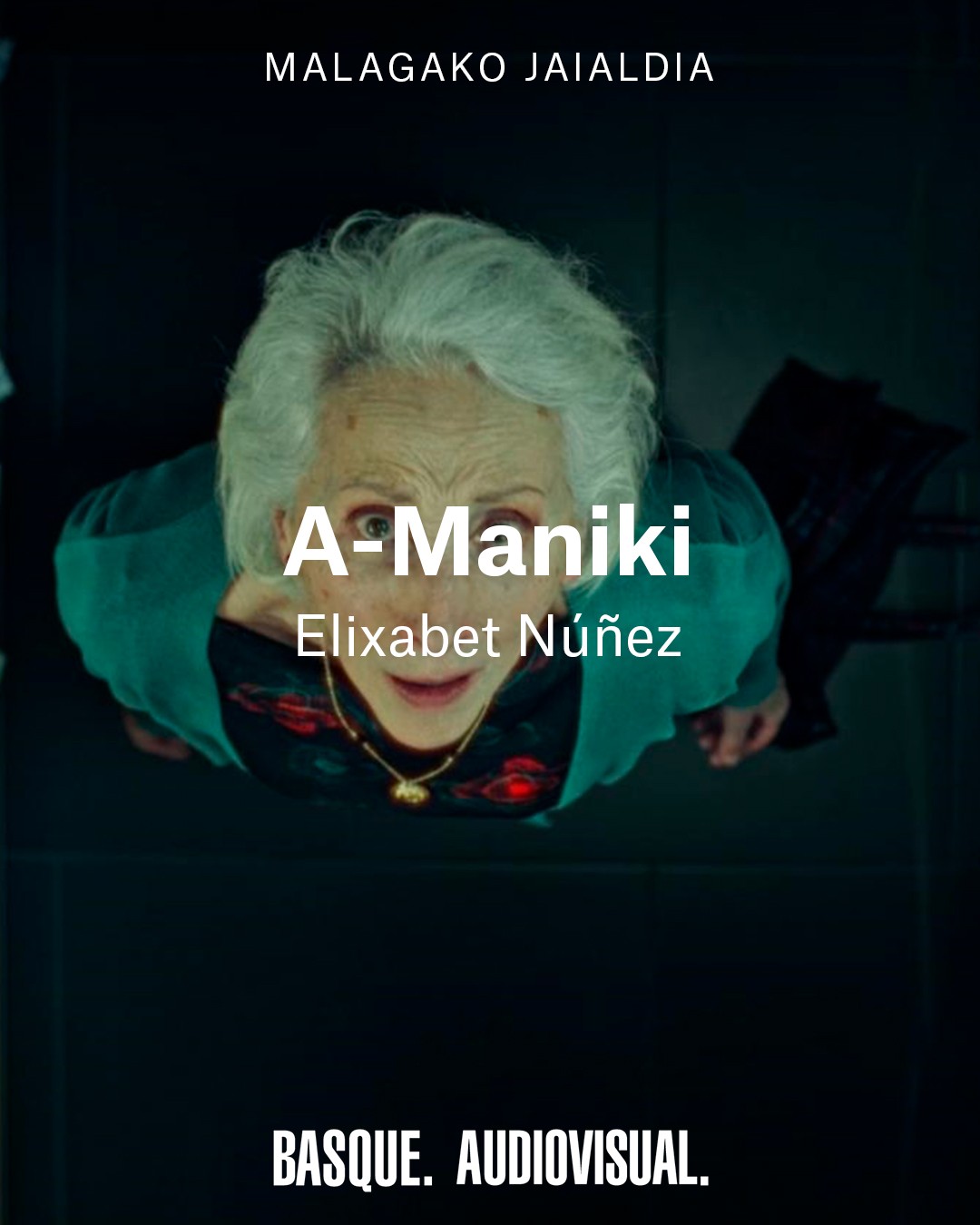

The film premiered in Malaga and received the Audience Award. How did you experience that reception from the audience?

When I presented the film in Malaga, I asked the audience to set aside the head that thinks and stay with the head that feels — in other words, to move away from ideas, ideologies, and simply let themselves be carried by emotion. During the discussion, I saw that people were deeply moved. When I heard about the Audience Award, I wanted to believe they had taken me at my word.

Now you’re preparing to present it at the San Sebastian Festival. How did you receive the news, and what does it mean for you to show your film there?

It will be a second chance in Spain. In June, I accompanied ‘8’ to the Guadalajara Festival in Mexico, and once again, after giving the same introduction I had in Malaga, I saw the audience deeply moved. At the end of June, at the vibrant Mediterranean Film Festival in Malta — where it won the Best Screenplay Award and the Special Jury Prize — I felt the same again: if ‘8’ is watched without overthinking it, simply feeling it, letting each person make the story their own in an intimate way, it has the power to ignite something deep within, wherever it is shown. I hope — and I’m truly excited — that something similar will happen again in Donosti, in my city.

Looking to the future, do you have any projects in the works that you can give us a preview of?

I am preparing a very ambitious project entitled ‘Jai Alai’; the story of the relationship between two Basque pelotaris, father and son, who went to play cesta punta in Miami during the 1970s and 1980s.